Integration

Insertion

Addition

Form of Intervention

The relationship between the existing and new construction can say a great deal about values attributed to a project. The way in which the new construction interacts with the existing fabric is an essential design decision driven by many exterior factors, such as the historical and material value given to the existing building as well as the existing condition presented by the structure. A large factor as well is the pre- existing spatial organization and volume presented by the building. If the new program being introduced to the building is too large for the existing fabric, the design will address the problem accordingly.

The forms of interventions can be categorized into three distinct approaches: Integration, Insertion, and Additions. Although these ar approaches to analyzing a rehabilitation project, they could also apply to any of the other three conservation strategies discussed earlier. These forms of interventions can be strictly applied to a design project by themselves as well as, and most often are combined with one another to accomplish a desired objective.

Image 1-3

INTEGRATION

The first of the three interventions, sometimes the least abrasive and potentially least noticable of the three, is Integration. This strategy could also be termed weaving, as it is the seamless union of new construction with the old, working its way in and around the existing fabric to become completely dependent upon one another. These projects usually have limited space to begin with and are unable to accommodate new structures within the old building. Integration is typically more readable in exterior connections of buildings such as windows and doors, as can be seen in the detailing of Castelvecchio. Integration tends to be used in cases where the retention and focus is higher on the existing fabric of the building. Respectful integration of the new interventions is key to a successful and harmonious design. Carlo Scarpa’s designs are masterful in the integration technique. The viewer is almost unaware of where the new building begins and where the old ends.

The designer for the museum at Castelvecchio Carlos Scarpa chose to make minimal alterations to the existing fabric. Instead, according to Byard (1998) “Mines it, in both the geologic and the military senses, for space and meaning…committed to the existing building as a source of value to be explored, understood, and developed”(p.27-28). You can see through series of reveals where Scarpa inserted his own work into Wren’s work on the original fabric of Castelvecchio. The small reveals grow larger and larger until they culminate at the largest reveal where Scarpa removed two joining walls of the castle for an outdoor gallery space made up of various platforms and cantilevers. Here the insertion of new materials look as though they have always been the true structural forms within the walls holding up the building, and it wasn’t until Scarpa came along that the materials where exposed. This is not the reality, but the successful integration of the new intervention within the historic building makes it appear as truth.

The fact the Scarpa was so successful at combining the old and new into one work of architecture could be seen as detrimental in the eyes of conservationist if the work is not displayed as new and old. Due to the nature of integration, if the new and old are not distinguishable enough, the effect this could have on the understanding of the buildings narrative could be lost. The design should allow for the distinction of what was there and what was added for purposes of future alterations as well as clear understanding by the view, so that they do not get a false sense of the historical fabric.

INSERTION

Image 4

Image 5

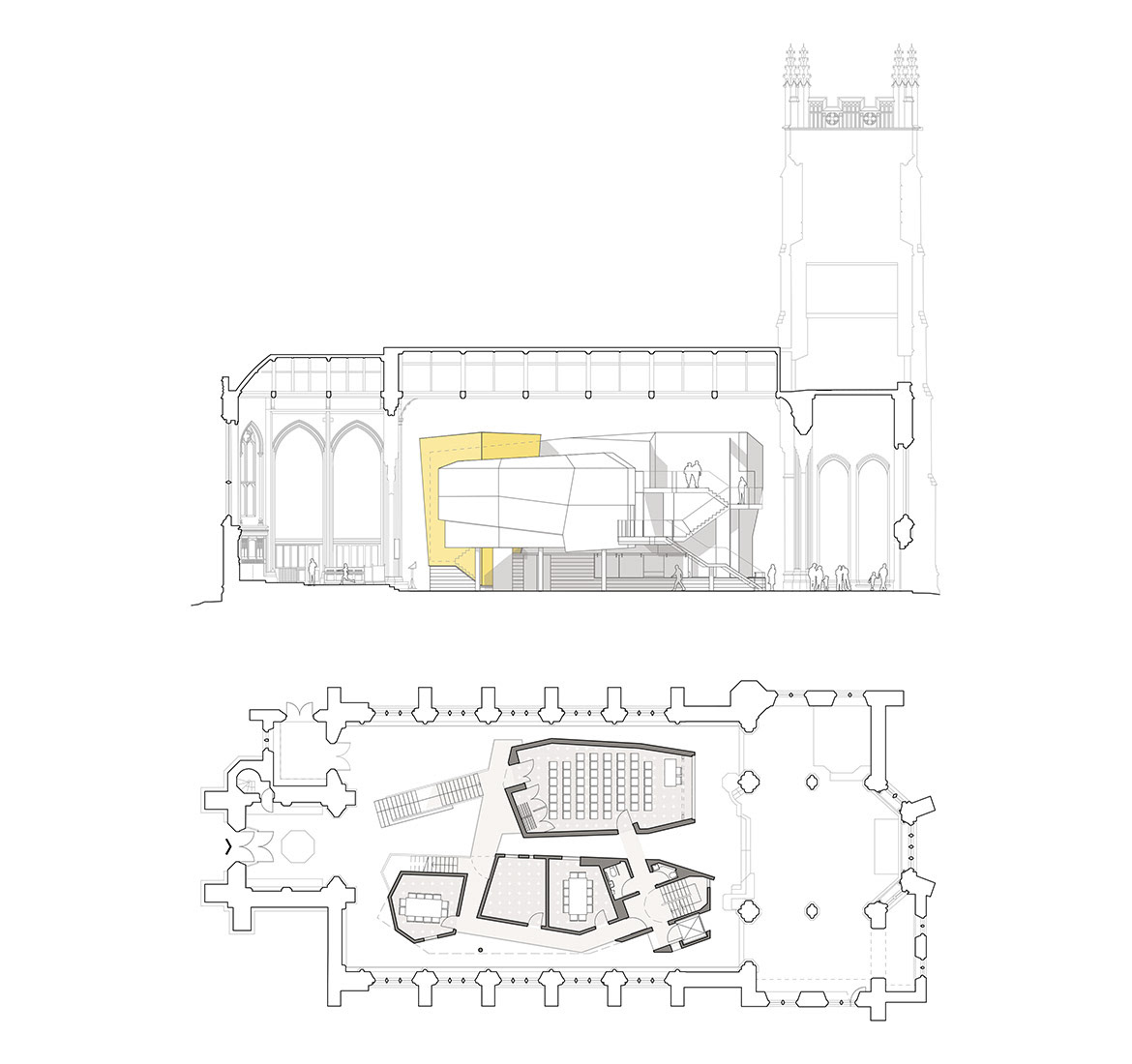

While similar in many ways when executed properly, Insertion is the execution of placing a modern structure within the existing fabric to allow for the proper spatial organization for a new program. Some approaches to the intervention of insertion are more visible than others. One approach to insertion is the placement of new elements within the existing structure such as all Souls Bolton in Bolton. This approach allows for the exterior of the building to remain untouched in most cases, which is highly sought-after when dealing with properties that are within historical districts where the original exterior facades are sought-after.

Insertion is used, like previously stated, if the exterior facade is seen as a important value for the project and is therefore wanted to remain untouched and given high priority. On the other hand, if the original interior fabric of a building is too damaged or not there at all, insertion has much more freedom to explore the degree of intrusion to the existing building. Insertion also helps to subdivide the original spatial organization of a building if needed to serve the new program. It is a way of adding modern circulation into a historical building which might not be up to date on all code requirements needed to function as a “new” building. A good example of this kind of insertion is The Ondaatje Wing at the National Portrait Gallery in London England.

The new addition in 2000 added two new galleries, a lecture hall, staff facilities, and a rooftop restaurant, but, most importantly, it added a new major circulation route through the building. The new circulation allowed for the simplification of movement through the building, which before, for the visitor, was maze-like, winding through several rooms in order to locate the main staircase. With the insertion of these new programs within the old service yard, the visitors have a clear and straight path to all gallery floors. If done poorly, insertion is sometimes seen as a false sense of pointless preservation of a shell. These cases typically arise when the existing fabric is seen as a exterior second skin that has no function but to allude to the past and hide the modern building, thereby most likely only preserved for the aesthetic values and not concerned with any other value.

Image 6

ADDITION

Addition as an intervention approach gives the designer the greatest freedom of the three, but comes with more decisions which impact the overall narrative of the design. Addition is the joining of new and old to create a new building, although the joining of the new building to the old structure may not alter the existing structure, even being separated all together, or join at the side like the British Museum’s World Conservation and Exhibition Centre. It will impact the narrative and aesthetics of the site, which is why the juxtaposition of the two structures in this intervention is critical. In some cases additions can have an overlap with insertion in that you could consider the addition of a new building within the old structure as the addition, as is the case of The Ondaatje Wing at the National Portrait Gallery. Additions allow for interaction to further reinforce the old building as a key component or for the new building to hint at the pre-existing. Additions allow for historic buildings to accommodate for larger programs where they may not have been equipped to do so prior to intervention.

There are many examples of addition treatment. One such project is by Reiach and Hall Architects in Stomness, on Orkney Island in the United Kingdom. Here this intervention was accomplished while still preserving the historical narrative and valued attributes of the existing building. The new design for the addition of the Pier Arts Centre appears at first glance as a modern building adjacent to the existing stone structure it is attached to. The addition takes on the shape of the existing fabric of the site while departing from the historic context in its material selection. The designers were challenged to make a building which in one way appear heavy in mass like the existing stone building as well as light and invisible, not to disrupt the existing fabric. This was done by making the facade facing out towards the bay solid, presenting a modern reflection of the old building beside it. The other elevations of the building appear light and almost vanish in the existing fabric by being derived from altering opaque and transparent materials. The addition distinguishes itself from the historic fabric while maintaining its connection and relevance to the sites fabric.

In order for an addition to become successful, it must respond to its existing counterpart as well as to itself, as accomplished through replication as well as contrasting the old. It is very hard to begin to meaningfully discuss the impact addiction has on the sites narrative without the discussion of the expression this intervention begins to take and how that expression relates back to the existing fabric of the site.

Replication

Allusion

Opposition

Expression of intervention

The rehabilitation of a building takes into consideration the structure itself as well as the new purpose. There are four basic expressions, according to Semes (2009), an architect can consider when deciding which strategy best fits a location and its purpose. Combining the old with the new can be a literal replication, invention with a style, abstract reference or an intentional opposition. The differences between the four are a matter of the “balance between the values of differentiation and compatibility” (Semes, 2009, p. 173) Although these expressions of design are intertwined with the three forms of interventions and are interchangeable with each approach, they tend to be most noticeable when there is a addition to the existing structure, and therefore arguably play a larger role in design decisions in those contexts.

Image 7

REPLICATION

Literal replication has been disapproved by many contemporary theorist as creating a false narrative as it sets out to expand the existing structure with a exact replication of the forms, materials and style. It strives to create a “seamless intervention” to the original, and, if done so correctly, can sustain the character of the existing fabric and site. In order to accomplish this goal, the new design must respect and accommodate the existing scale of the building, not to overwhelm it or the surrounding context. Literal replication has been used throughout architectural history as a way to retain a public space’s appearance and volume. Some of the great European and American urban spaces owe their experimental value to literal replication over many decades. Piazza Santissima Annunziata is a good example of how a urban space has benefited from literal replication from numerous different designers and time periods; from its first major construction between1419 and 1424, to its last exterior intervention between 1601 and 1607.

A more contemporary illustration of literal replication can be found at the former Felix Warburg residence, now the Jewish Museum in New York City. The 1908 mansion was designed by C. P. H. Gilbert in the French Gothic-Revival for Felix Warburg. In 1945 the mansion was converted into the Jewish Museum, and in 1993 the museum was in need of more space and decided to expand into the former sculpture court. The museum’s director and the architect agreed the mansion itself was part of the identity of the museum and therefore, after exhausting other ideas,found that the best approach to the addition would be to replicate the architectural elements in the new design. Some of the original elements where even removed from the existing structure and incorporated into the new wings design. Unlike the Piazza Santissima Annunziata, the Warburg mansion is not a repetition or mirroring of element extended from the existing structure, but a new “composed” structure which duplicates the materials and details found in the old mansion. The extension received mixed reviews when completed in 1993 by the preservation community. Some argued the building was a misleading representation to the public and did not set a good example of distinguishing past from present, leading viewers to believe that the whole complex was designed and built by the same hand.

ALLUSION

Image 8

When the conservation of a site doesn’t want to replicate the original design elements, they may look to the strategy of invention. This is the design of new interventions which does not copy the existing building, but uses new elements within the same style or something closely related to that style. When used correctly the design should “sustain a sense of general continuity in architectural language,” therefore “achieving a balance between differentiation and compatibility” (Semes, 2009, p. 187).

An example of the use of invention within a style is the Henry Clay Frick mansion in New York. The Frick mansion is now home to the Frick Collection of art and has gone through two major interventions which both demonstrate mastery of the invention approach. The original house was designed by Carrere and Hastings in 1912 and based on a Parisian townhouse. The house later became a public museum in 1931 and was added to by John Russell Pope. Pope rearranged the interior of the building to accommodate for the new program as well as inserting new elements to further organize the interior. Pope also added a new structure which was to house the art reference library. This addition along with the intertwining of new elements within the building were both designed to reflect the existing fabric designed by Carrere & Hastings as well as introduce his own contribution to the overall project. As described by Semes (2009) the two buildings are intertwined in such a way that it can be difficult to find the junction between the two buildings.

Hastings brought a strong French classical sensibility to his work, as well as an ornamental richness and delicacy, reflecting his training at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts. By comparison, Pope’s taste is more austere and neoclassical. His genius lay in abstract massing in unornamented surfaces. For the Frick Collection, Pope tempered his own instincts, achieving continuity by means of a shared language and a great sensitivity to scale. Differentiation came as the natural and inevitable result of the different sensibilities of the two architects. (p. 204)

The addition in 1970’s by Harry Van Dyke, G. Frederick Poehler, and John Barrington Bayley followed Pope’s footsteps in designing a intervention which was respectful of both the original structure as well as the second addition. This was accomplished by using the same materials, following the horizontal organization laid out by the original 1912 mansion, and using the same ionic orders in the detailing. Where the building departed from the previous two structures in design is the bolder approach Bayley took with the detailing, emphasising features which Hastings and Pope refrained from in their designs. For invention to work properly, it is important for the buildings to refrain from changing scales, materials and formal language, while it does allow for more opportunity than literal replication to embellish subtle variations into the design, making the new work distinguishable from the old.

While literal replication and invention strive to combine the new building to the old, and are in some ways two varying ends of the same range of philosophy to achieving unification between the two, the Abstract Reference strives “to balance differentiation and compatibility” with a stronger emphasis on differentiation (Semes, 2009, p. 209). This approach seeks to maintain the visual continuity of a particular tradition architectural style while not reproducing it, resulting in a traditionally styled building constructed with modern materials and details.

One such example is the intervention at the Goteborg Law Courts in Goteborg, Sweden. Designed in 1937 by Eric Gunnar Asplund, the interventions was an addition and insertion to the existing 1672 court house designed by Nicodemus Tessin. The building had become too small to function properly as a courthouse. The building is prominently located at the town’s main plaza, making it a landmark for visitors; meaning the intervention was no small task. The addition to the building reflects the existing building by pulling vertical lines from the building’s facade and continuing those lines across to the new volume that was added. Asplund also kept the horizontal rhythm of the existing building continuing it onto the addition. He then brakes from the rhythm of the old building by offsetting the windows towards the old courthouse, creating a narrative that the old courthouse is still the home of justice and importance in sweden and that the new “box” is a modern foundation which is a reflection of that justice system. (Byard, 1998)

Similar to the Goteborg Law Courts, the addition at the Gladstone Library in Toronto, Canada by RDH Architects is designed with an abstract reference approach. The addition, which extends off the side of the building, shares only a limestone base which looks as though it extends directly from the existing building. The remaining addition is made up of transparent faces, distinct from the historic building. What the designers decided to do was not reference the existing buildings material pallet, but distinguish between new and old with different materials and reference the old building through mimicking the vertical and horizontal proportions in the new material.

Image 9

OPPOSITION

Contrary to keeping with any tradition is the intentional opposition strategy sometimes. With this practice the goal is to depart from the character of the existing structure. Elements of contrast and differentiation are used to reach this effect. The materials or style often do not seem compatible, which ironically often make for the best fit in reaching the goal to change or update the purpose of the building. An example where this strategy works are the Jewish Museum in Berlin and the Hearst Tower in New York. Both examples depart from any direct connection between the existing fabric and the new intervention. This expression of intervention can create a clear narrative of what is new and old, but can easily overpower the existing building like it does in the two examples, almost leaving the viewer wondering why these new forms are expressed in such a way. The narrative this kind of expression can make, like the Idea Exchange in Toronto, Canada, is to indicate which building houses the new modern program and which has retained its original program. This expression would be a poor design choice if the goal of the project is to preserve and present the historical building as the main value. But if the goal is to celebrate the new and use the existing fabric as a foundation which is in support of the present, than this approach to design may work.

The designer must choose the forms and expressions used in a project carefully. They must choose these approaches based off of their conservation goals and what society finds to be valuable in the existing fabric. If not considered and thought out well enough, “The city is in danger of becoming little more than a theatre, the real buildings hidden behind the stage sets of the retained facades.” (Brooker & Stone, 2004, p. 10)

The designer must choose the forms and expressions used in a project carefully. They must choose these approaches based off of their conservation goals and what society finds to be valuable in the existing fabric. If not considered and thought out well enough, “The city is in danger of becoming little more than a theatre, the real buildings hidden behind the stage sets of the retained facades.” (Brooker & Stone, 2004, p. 10)